There are a number of skills and methods that are useful when you're trying to have more collaboration and/or to reduce the level of conflict in the parish. Collaboration is probably the hardest conflict management style to use because it requires more skill and emotional intelligence than other styles. Collaboration calls for a high level of assertiveness and an equally high level of cooperativeness. You are trying to address both your own concerns and those of others.

Collaboration: Easy to be in favor of--hard to do in practice.

To get collaboration you need a positional leader and a critical mass of people with the required skills and the stance. Possibly the most important skill is learning how to seek the positive and underlying concerns of the parties involved instead of jumping to a position.

To get collaboration you need a positional leader and a critical mass of people with the required skills and the stance. Possibly the most important skill is learning how to seek the positive and underlying concerns of the parties involved instead of jumping to a position.

Our tendency is to start with our position on an issue. We explain what we want and why what we want is reasonable and just. Our positions are usually rather specific.

Interests or underlying concerns are what sits within or under the position. Most people find it difficult to identify their interests as they tend to be elusive. They are connected to our hopes and dreams, our fears and anxieties. At times we resist exposing them because we fear we will not get what we want in the situation. We fear that letting others know will make us vulnerable.

Our positions are what we want. Our positive underlying interest is what we need. As in “We want the parish to have ten minutes of silence in the Sunday Eucharist” vs “We need less rush and business in our lives; more calmness and stillness.”

An example

I had a consultation with a small parish on a Maine island. I worked with them off and on for several years. I facilitated their vestry retreat and a few whole parish conversations and worked with their parish development team. They were a fairly cohesive group with a desire to become healthier—deepen their spiritual life, add a few more year-round members, and so on. They also wanted to address a few issues--Managing the shift from a small year-round congregation with an average attendance of maybe 20 and a summer congregation of 80 or 90; not having their own building and the impact of that on activities, membership growth, and being trusted on the island (for most islanders the lack of a building signaled both instability and oddness; “you’re all very nice people but you don’t have the same stake as other churches.")

This example has to do with a small thing – the longing for, and fear of, silence.

During a vestry working retreat I had them break into small groups. They exploring their “likes and concerns” about the parish. I wandered from one group to another. It was all fairly routine stuff. In one group a person said, “I’d like to see more silence in the Eucharist. It feels rushed to me.” To my surprise everyone else in that small group quickly agreed.

When the whole vestry was again gathered I had the groups report on their conversations. The group I had been observing included the desire for more silence in their sharing but didn’t indicate the emotional investment that had been expressed. I decided to raise that and to test the issue with the whole vestry. Here’s the result.

Regarding more silence and stillness during the Eucharist.

|

I’d like a lot less |

|

|

|

|

I’d like a lot more |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

/ |

/ |

/ |

///// //// |

The vicar was stunned. He talked about how it never occurred to him to provide much silence and stillness in liturgy. Apparently in his last parish it faced several very upset members when he attempted to introduce it. He was temperamentally a cautious person. He expressed his concern that some in the parish might be upset if we introduced more silence. Even though anxious he was prepared to move forward.

I suggested that they enter into this with a stance of experimentation and action-learning. We decided to go ahead and introduce it and after four months to assess how it was working. The vicar was to work with a few people on how to introduce it. They provided for silence before beginning the Eucharist and after the sermon.

I suggested that they enter into this with a stance of experimentation and action-learning. We decided to go ahead and introduce it and after four months to assess how it was working. The vicar was to work with a few people on how to introduce it. They provided for silence before beginning the Eucharist and after the sermon.

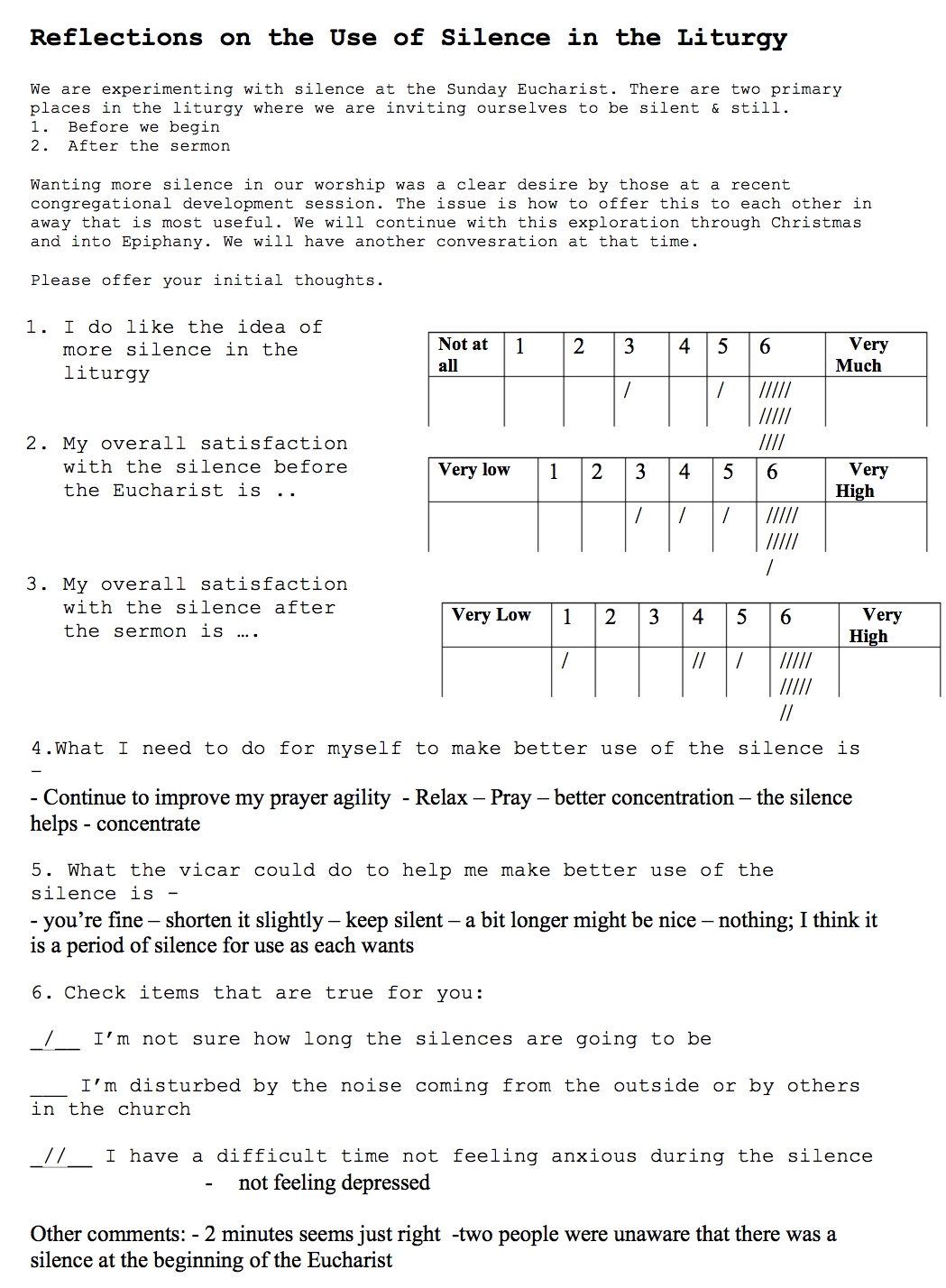

The assessment four months later involved having people complete a brief survey and then we discussed it at coffee hour. Here’s the survey.

At coffee hour we made some attempt to have people speak to their positive underlying interest. One person did acknowledge that he felt disturbed during any silence. A number of others talked about how it helped them experience the liturgy in a calmer and more grounded manner.

At coffee hour we made some attempt to have people speak to their positive underlying interest. One person did acknowledge that he felt disturbed during any silence. A number of others talked about how it helped them experience the liturgy in a calmer and more grounded manner.

In a follow up meeting the vicar had to deal with his anxiety about the two people having the most difficulty with the silence and stillness. Others listened to his concerns while urging him to stay with the change. In response to the concerns of a few the vicar became more disciplined about the length of the silences (so people knew roughly how long they would be) and he offered to meet with anyone having difficulty to see if he could help them deal with the anxiety or depression they felt during silence.

By the time they checked in after Epiphany the congregation had settled into the practice.

Figuring out positions and positive underlying concerns

Positions are solutions. The are descriptions of what we want – “I want more silence in the Sunday Eucharist.” Or “I want no silence in the Sunday Eucharist.” If our feelings are strong and we have lost patience they may take the form of demands or ultimatums. For example, “If we continue with this practice I may need to go to another church.” Or, “This could damage my emotional health. Do you all want to be responsible for that?”

To figure out the positive underlying concerns in a disagreement

You might begin with yourself. Look for your own interests. What is your longing or fear in the situation? Understanding your own concerns are just as important as understanding those of others.

Early in this process I invited people to share what they got out of having more silence and stillness? I repeated that invitation each time they discussed it. Over time they increased their skill at sorting out positions and positive underlying concerns.

To identify the interests of the others you need to do things such as:

- Ask them what is the concern under or within the position they are taking. “I understand that you’d like more silence in the liturgy. Could you share what impact such silence has on you?” You’re not asking for the person to make a case for their position. You’re trying to understand their needs in the situation.

- The stance needs to be empathetic. You are trying to understand the person’s hopes, fears, anxieties, and needs.

- It may help to ask open ended questions or about feelings – “Will you share how silence sometimes cause anxiety in you and at others times peace?” or “What do you think will happen if we increase the amount of silence and stillness?”

- Be especially alert for basic needs being expressed – safety, sense of belonging, impact on relationships, issues of personal or parish identity and integrity, sense of accomplishment and competence, a longing for holiness and wholeness of life.

This takes a lot of time

Collaboration takes more time than any other approach to conflict management. Parish leaders need to decide if the issue is worth the time. That will often depend on what other pressures are being experienced by parish leaders and more generally how well those leaders manage the parish “demand system.”

I think the parish stayed with the issue of silence and stillness for two reasons. Most of the members wanted more silence in their worship. I, their consultant, offered safe, structured ways to address it.

An opportunity for learning

So, why did I do that? Why did I enable them to spend so much time on the issue? My approach to pastoral and ascetical theology and practice does have a strong bias toward liturgy with flow and grace, beauty and balance. I see silence and stillness as an element of that. But the more important reason for me had to do with wanting them to increase their skills for collaboration. For them this was a relatively low threat issue. People aren’t very open to learning new skills when the issue being faced has the potential to create a higher level of conflict. This was a perfect opportunity for learning the skills and stance of collaboration.

rag+

Resources

An Overview of the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI)

Distinguishing Between Compromising and Collaborating