The "People's Procession" to Communion

Thursday, January 31, 2013 at 10:55AM

Thursday, January 31, 2013 at 10:55AM Given the centrality of the Eucharist in our lives—and in our parishes—I’ve been reflecting on a basic question: how do folks get from the pews to the altar for communion, and what are the formation implications in how that happens? In my experience, this one issue—which can seem sort of trivial on the surface—gets at a whole host of assumptions about dependency, competence, and formation.

There are parishes where, as soon as the celebrant says the words, “The Gifts of God for the People of God,” (or similar words of invitation) the people head to wherever they need to go to receive communion. The ministers of the altar will be receiving communion themselves and finishing up a few things, but the congregation is nonetheless moving forward simultaneous with these activities. It is clear that the process is understood and owned by the congregation.

There are other parishes where this procession to communion is mostly orchestrated by the “usher” team and the timing and flow is dependent on how the ushers direct those in the pews. This may be relatively low-key, or it may involve significant directions and usher involvement (also referred to as “the block-and-tackle”).

Sometimes, if the usher team is new or missing a member, the cues to the congregation won’t happen and there will be a delay in parishioners heading up to the altar. Heads turn, there is quizzical raising of eyebrows, and a sense of confusion and hesitancy reigns until someone takes charge and lets people know what to do. You may also see variations Sunday to Sunday, depending on who is filling the usher role. The underlying theme, though, is consistent: moving forward to communion is properly controlled by the ushers and is not a job that can be reasonably left to the judgment of the members. Just imagine the chaos that could be unleashed! (Note: I don’t blame or criticize the ushers for this. It’s a parish-system issue and ushers are just doing their jobs. It is in turn the job of the clergy and other leaders to pay attention to the health of the system overall, including thinking through the component parts.)

In my day job I enforce compliance with regulations, so let’s take a look at what the Prayer Book has to say about this, shall we? It specifies that the priest is to receive communion “while the people are coming forward.” Another instruction says that the “ministers are to receive the Sacrament in both kinds, and then immediately deliver it to the people.” Simple enough, but in most cases the functioning of the ushers acts to delay the people coming forward.

In general, I think it’s important to pay attention to the rubrics, but in this situation there’s a reason that goes way beyond tradition or rigidity and speaks to something important and powerful in the experience of worship. When we assume members of the congregation can get to communion on their own, we encourage them to be more actively involved in the liturgy and to take ownership of their participation. We provide a real-life place of responsibility for our own spiritual lives.

So why the differences in the way parishes handle this? Why do some manage going up to communion without any need for “staff” and in others it seems that no one would move at all if they weren’t prodded?

My guess is that there are three basic reasons: One is that parishes where the members simply go up on their own have a high degree of competence with participation in the Eucharist. They are used to owning their participation and they understand the basic rhythms and content of the service. The clergy in these parishes encourage that sense of ownership by intentionally building competence and by refraining from behaviors that reinforce dependency. They don’t give instructions in general and they don’t give these instructions specifically.

(A side note on this: Bob Gallagher and I recently visited a parish in Georgia where the congregation was small, made up mostly of retirees, and clearly populated with long-term Episcopalians. They were quite welcoming, had a clear service leaflet that provided enough information for visitors and members alike, and the service would have been surprisingly good except for the constant stream of directions from the priest. Really. Page numbers, introductory explanations to liturgical acts, stand up, sit down, kneel, share your toys, don’t eat snack until everyone has some—you get the drift. Interestingly, though, there were no ushers and absolutely no instructions about coming up to communion. The congregation just did it. Despite this obvious competence, however, the priest mentioned that he is actively recruiting ushers! It was clear that once he has them, they will be used to direct and control the communion procession. Argh! Back to the three reasons…)

The second reason is our mental models. The use of the word “usher” itself implies a certain gate-keeping function. At the opera, the usher is there to help you find your seat, make sure you don’t sneak into the better seats, to shush you if you’re talking, and perhaps prevent your entry if you arrive late. This image of the role doesn’t help much in the parish church and may lead to some underlying confusion about the degree of control to be exercised. In fact, in the parish, what we often call an usher is really a greeter and a facilitator of entry—and “Greeter” is probably a more accurate title. Yet, simply changing the title without helping people understand the differences in function—and how they should actually behave differently in the two roles—doesn’t do much good.

The third reason is that nobody suggests we do it another way. It simply doesn’t occur to those involved in the ministry to think about the consequences of control and direction at this critical point in our worship. Clergy may assume that they will hurt people’s feelings if they bring it up, that there’s not a useful alternative to “the way we’ve always done it,” or that there’s simply no practical and effective way to help the parishioners and greeters learn a new way.

I’d like to offer some alternatives, as well as a way to think about this as an aspect of spiritual growth.

First, how do we best greet people and facilitate entry? Certainly we want to be helpful and friendly. Much of that takes place before the service even begins as we make sure parishioners and visitors have service leaflets, know how to get to the restrooms, where to go if they’re interested in church school, and generally assist with mobility concerns. This requires some broader prep work that will go beyond the specific duties of the greeters. It is a worthy area to spend some time on with both the clergy and a cross section of parishioners.

Second, do we have adequate signage? Is it clear how to access the elevator or ramp? Where the restrooms are?

Third, do our service leaflets themselves give enough information, such as page numbers, a description of the materials used (e.g., spelling out Book of Common Prayer, and maybe indicating the color of prayer book versus the hymnal), and an invitation to relax and rely on the rest of the congregation if you’re not familiar with the traditions of the Episcopal Church[1]?

With communion specifically, is there enough information in the service leaflet so that those who are new will have a good sense of how it works? A simple notation that the people move forward at the invitation is usually enough. Most of the time, visitors don’t sit in the very front pews, so they can safely rely on cues from others and follow along.

If the parish needs to direct traffic flow in a particular way, again a basic indication of that in the service leaflet may suffice. For example, the following could be written at the appropriate point in the service leaflet: “Please approach the altar from the center aisle and return through the doors on the left and right of the altar, returning to your pew by the side aisles.” Again, most people will be able to get the gist from watching others.

Another practical issue is that it may happen that some folks are not moving forward to the altar. This could be because they don’t receive communion, because it will be brought down to them later, or because they weren’t certain about what to do. In any event, those behind should simply move forward without waiting any longer. Those in front will be able to catch up, if that’s what they need to do.

Greeters can be coached in a relatively brief session and the process can be reframed. The rector can make some simple announcements over a few weeks letting people know that the parish is changing the way it handles the procession to communion. Those who sit right up front can be invited to help with the transition by moving forward promptly, thereby signaling those behind them by example.

Beyond these issues, though, I want to suggest that making this change is an important act of spiritual formation. In developing our own spiritual lives, we need to know how to participate in our central practices. We are a Eucharistic people, a Eucharistic community, and if we are cajoled, controlled, or otherwise minutely instructed about the primary act of our communal worship, we are receiving implicit, unintended, messages about our capacity to be responsible for our spiritual lives.

There is a major disconnect between the celebrant’s joyful invitation to the altar and the subsequent instruction to sit back down and wait your turn. Watching people head up one-by-one reminds me somehow of the group inoculations I was subjected to as a kid—we’d hang out en masse in the school gym, and then we’d each get our shot in the arm when our name was called. To me, the inoculation image runs directly counter to the power of the Eucharistic prayer that asks that we “be delivered from the presumption of coming to this Table for solace only, and not for strength; for pardon only, and not for renewal. Let the grace of this Holy Communion make us one body, one spirit in Christ, that we may worthily serve the world in his name.”

Howard Galley, in his book, The Ceremonies of the Eucharist, writes: "The approach of the people is properly understood as a kind of procession: those in the front of the church going forward first, followed by those in the seats behind them in a steady stream. It is far better that there should be many people waiting in the aisle than to create the impression that the communicants are approaching in 'groups' or 'blocks' of individuals."

Our participation in communion should emphasize the congregation as representative of the Body of Christ, and also speak to our eagerness to participate in the Sacrament—the people's procession, spilling out into the aisles on our own volition, active participants in the liturgy. The difference in energy is extraordinary. The aisles full, the Body of Christ together in all its divergent parts, a profound physical expression of what Robert Webber described as the meaning of sacrament in its broadest sense: “…everything in life points to the center, to Christ the Creator and Redeemer in whom all things—visible and invisible—find their meaning.”

Michelle Heyne

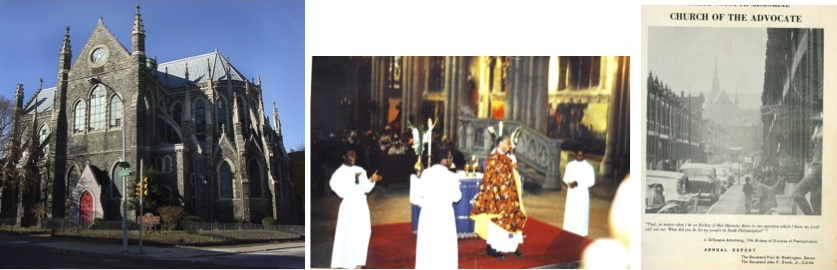

Instructions to ushers/greeters

[1] See, for example, St. Paul’s K Street, in Washington, D.C. The parish is known for its beautiful Anglo-Catholic style of worship. The parish is careful to preserve the dignity and integrity of the liturgy by not cutting across it with extraneous instructions, but it is also careful to be welcoming and affirming of those who aren’t yet familiar with their worship. Their service leaflet says something about allowing yourself to be carried in worship by others.