Collaboration 201

Wednesday, October 7, 2015 at 10:30AM

Wednesday, October 7, 2015 at 10:30AM Collaborating has costs. It requires a lot of time and energy. And that means the parties involved need to have the willingness to engage in structured conversations. We need to be willing to work face-to-face with those we disagree with and to listen to them. Another possible cost is that those involved may suffer stress and emotional pain. Collaboration calls for vulnerability and vulnerability carries the risk of feeling weak and exposed. To be vulnerable is to open yourself to the possibility of hurt.

An example –

It’s an Anglo-Catholic parish. A dispute has developed over whether to use incense at all primary liturgies (9 and 11 am). It’s a debate that erupts in some parishes during times of transition or stress. The debate usually takes shape along these lines -- "there are some people in the parish who are allergic to incense and therefore we should not use it." The response may be, "we have used incense for many years and that is part of the tradition here at Saint Mary's." There are variations on and cases to make related to each position.

It’s an Anglo-Catholic parish. A dispute has developed over whether to use incense at all primary liturgies (9 and 11 am). It’s a debate that erupts in some parishes during times of transition or stress. The debate usually takes shape along these lines -- "there are some people in the parish who are allergic to incense and therefore we should not use it." The response may be, "we have used incense for many years and that is part of the tradition here at Saint Mary's." There are variations on and cases to make related to each position.

Stepping aside from positions and looking for our positive underlying interests

By focusing on positions we tend to set ourselves up for a win-lose outcome. Someone gets to have incense or they don't. Or maybe there is a compromise in which we use incense on major feast days and one or two seasons of the church year but not at other times. Compromise by definition means both parties walk away unhappy. Sometimes it’s the best we can do but by its nature a compromise is an unstable solution. Because we want to be able to be together as a community we all need to accept the compromise. People remain dissatisfied and usually a time comes when the issue is reopened.

Collaboration is the path if we want both to get the issue off the table in the short term and also establish longer term stability while increasing trust and the abilities of leaders to manage differences. The skill at the center of that is our ability to identify our positive and underlying concerns and avoid jumping to a position. When the parties lock themselves into expecting a particular outcome it becomes much more difficult to keep conflict at a lower level and manage it effectively.

Seeking the positive underlying concern of each party involves empathy and a willingness to set aside for the time being our positions. If we are to collaborate and find or develop an approach that is more likely to be owned and sustainable in the parish we need to find within ourselves some degree of respect and love toward those with whom we disagree.

We need competence

We also need a few other skills to make collaboration work. Collaboration is not just a feeling or a hope but a set of skills, it’s a competency. For example, we need to be able to imagine the other person’s positive underlying concerns and withhold our assumption that they have poor intentions toward us and our concern. We need the capacity to clarify and share our own positive underlying concern and for the moment set aside are impulse to push a position. We need to manage our own emotions and any tendency to play the victim. And we need the skill to shape an integrative approach; in which we can adequately address the positive concerns of all parties. We need an integrative solution that truly respects the interests of the people with investment in the situation? [Note: in this work it is important that we not over-involve all those who have little investment in the outcome. If we do over involve them it's likely to tilt things to one side or the other and accomplish little.]

As people seek ways to express their positive underlying expressions there’s an exploration of the context, feelings and needs

On the one hand it does matter if people have allergies, especially if they don't have other reasonable alternatives for worship. In that case the positive underlying concern might be along the lines of wanting to feel valued, as though their well being matters. For others the incense might represent being part of a long tradition of spirituality in many religions, certainly in catholic expressions of Christian faith. This can be a matter of identity for some people. They may have a difficult time expressing it but the fact is that identity is usually upheld through various artifacts, ways of behaving and shared practices. So, if we let go of incense are we really Anglo-Catholics anymore?

It's easy for the conversation of underlying concerns to move into a place where each side attempts to dismiss the concerns of the others – “take your allergy pills, come to the early Eucharist where we don't use incense and it won't be lingering in the building or on the other side” or “you mean your sense of some abstract identity is more important than my health.” There will be no collaboration if we are focused on making the case for our position.

There are many, many issues around which these dynamics will play out in the parish church. Do we serve alcoholic beverages, ever? Should the vestry primarily focus on property and finance or share in the broad oversight of the parish? Do we express our concern for inclusion by having people receive communion before baptism and having people not baptized serve as wardens and vestry members or do we express our concern for inclusion by shaping a climate of acceptance with a clear and inviting pathway into baptism and communion?

In any disagreement within the parish there will be times when the outcome simply needs to be a win – lose result. There will be times when we simply need to suck it up and put up with the situation that makes neither side entirely happy. However, if what we want are outcomes where the decisions have a higher quality, where people find their relationships enhanced and strengthened, in which what we have decided upon is more sustainable, and in which we learn something about how to be together in community-- then collaboration is what we will work to do.

So, how might that parish approach the incense issue?

If the parish has three Sunday masses as they do at Christ Church, New Haven (8:00, 9:00 and 11:00) you could make the 9:00 am Eucharist always incense free and also maybe a bit less formal overall and the 11:00 am Eucharist always a high solemn mass with incense. Incense lovers at 9:00 could move to the 11:00; incense haters at 11:00 could move to 9:00. When a few complained that this was inconvenient the rector would need to say, “Yes, I do see how this is difficult for you. I ask you to be gracious and accept the arrangement as a good for our common life.”

If the parish has three Sunday masses as they do at Christ Church, New Haven (8:00, 9:00 and 11:00) you could make the 9:00 am Eucharist always incense free and also maybe a bit less formal overall and the 11:00 am Eucharist always a high solemn mass with incense. Incense lovers at 9:00 could move to the 11:00; incense haters at 11:00 could move to 9:00. When a few complained that this was inconvenient the rector would need to say, “Yes, I do see how this is difficult for you. I ask you to be gracious and accept the arrangement as a good for our common life.”

But if that’s all we did as an outcome it would be a compromise and not a collaboration.

What would make it a collaboration?

One element would be taking action that compensates or balances the situation. In the example above, if we decided to never have incense at 9:00 and to always have it at 11:00 that would address one element but not others.

So, if one of the underlying concerns had to do with maintaining Anglo Catholic identity we might take a series of actions to strengthen that identity by increasing practices of sacramental life and the formation processes that assist people to live that life—have a daily mass, schedule times for confessions, on Sunday have a priest at a side altar available for anointing as people return from communion, frequently have training in how to say the Daily Office and in contemplative and reflective methods

So, if one of the underlying concerns had to do with maintaining Anglo Catholic identity we might take a series of actions to strengthen that identity by increasing practices of sacramental life and the formation processes that assist people to live that life—have a daily mass, schedule times for confessions, on Sunday have a priest at a side altar available for anointing as people return from communion, frequently have training in how to say the Daily Office and in contemplative and reflective methods  included in the formation offerings, offer more quite days, bring nuns and monks in to lead retreats, arrange for silent retreats at a convent, and so on. The identity issue would seem to be an addressable underlying concern. The desire of some people to not have to go to mass at a different time is an example, in this case, of something that isn’t addressable.

included in the formation offerings, offer more quite days, bring nuns and monks in to lead retreats, arrange for silent retreats at a convent, and so on. The identity issue would seem to be an addressable underlying concern. The desire of some people to not have to go to mass at a different time is an example, in this case, of something that isn’t addressable.

That’s just one example of a possible result that would be an integrative solution in regard to the content of the situation. In itself it’s not enough if the parish is to gain the multiple benefits of collaboration. That requires more attention to process matters.

The second thing that would make the solution a collaboration is the process used to get to the result. If collaborative methods were used effectively the result wouldn’t just be the off-set of adding catholic practices but also increased trust, improved relationships, more confidence in our ability to manage disagreements and a few new skills and methods.

How do we set up a collaborative process?

Basic structure

Collaboration requires face-to-face conversation. It needs to be a structured conversation creating a zone of psychological safety. That safety is in part facilitated by providing a defined structure—stated outcomes being sought in this conversation, the anticipated sequence of activities posted in front of the group, a skilled facilitator who will keep control of the conversation by enforcing norms and coaching as needed. Psychological safety is also advanced by the competent use of methods, skills, and a climate and stance appropriate for a church.

Collaboration requires face-to-face conversation. It needs to be a structured conversation creating a zone of psychological safety. That safety is in part facilitated by providing a defined structure—stated outcomes being sought in this conversation, the anticipated sequence of activities posted in front of the group, a skilled facilitator who will keep control of the conversation by enforcing norms and coaching as needed. Psychological safety is also advanced by the competent use of methods, skills, and a climate and stance appropriate for a church.

The conversation needs to focus on those with an actual investment in the issue. People who don’t really have an investment in incense or no incense might be invited to be present but they should be observers and at most participant-observers (in that case they sit in an outer circle and maybe once during the session are invited to respond to a question like, “What do you hear as the positive underlying concerns of each party.”

Methods

Methods are the steps in the conversation based on sound theory and the wisdom gained from reflected upon experience. Related methods might include connecting exercises (maybe in the form of faith sharing), Force Field Analysis, Testing Process.

Skills

Effective collaboration calls for people willing to use basic communication skills – paraphrase, active listening, itemized response, making statements and rather than asking questions, and offering integrative solutions once they have heard and empathize with others.

Underlying theory

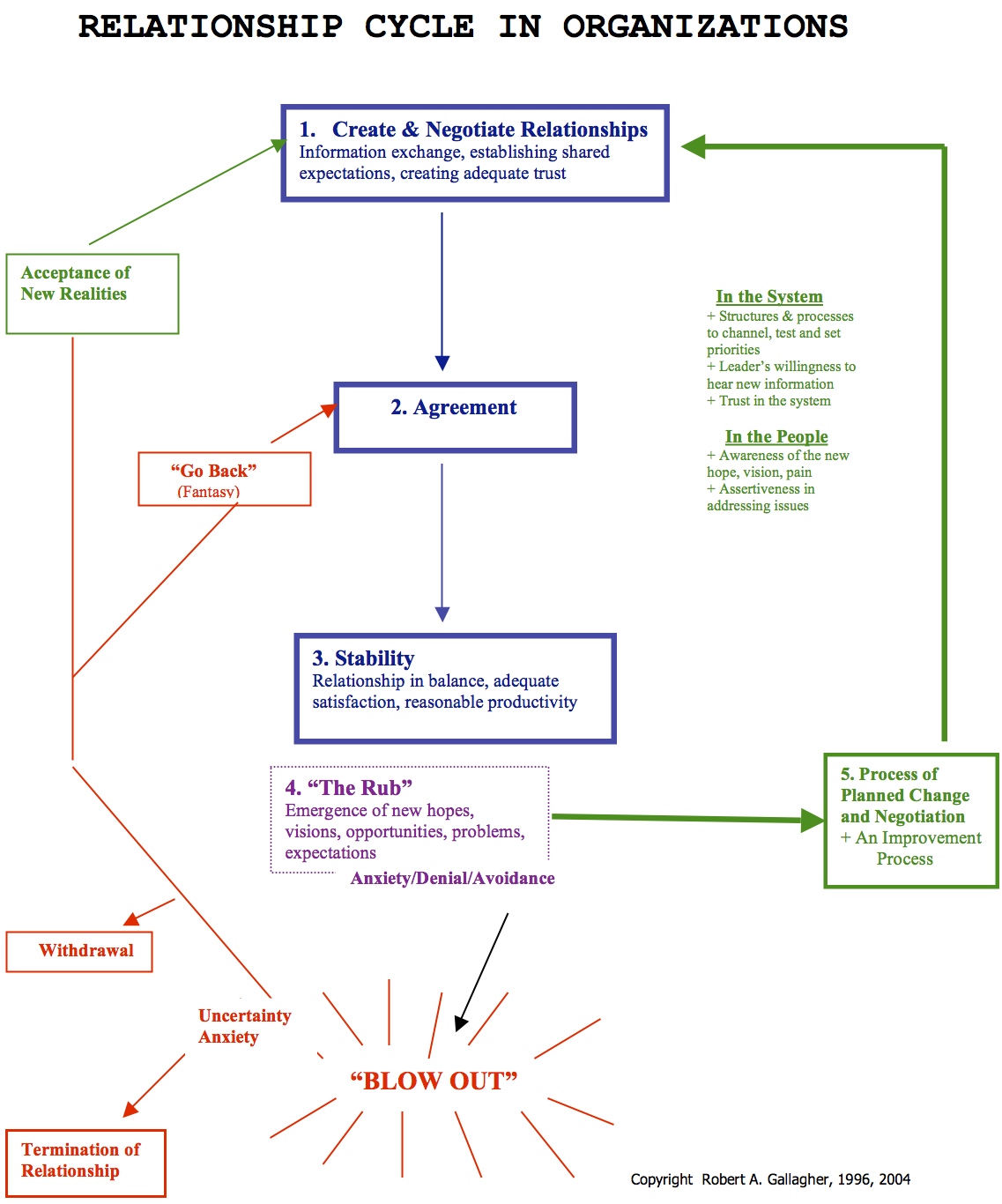

It helps if those leading a collaborative process, and a critical mass of those participating, understand a bit of theory. I use models and frameworks such as the Relationship Cycle, Intervention Theory, TKI, MBTI, Self Differentiated Leadership, and the Drama Triangle.

Appropriate and good theory helps us see more complexity in the situation than we might otherwise see. It also offers us a way of giving order to that complexity. That can allow leaders and participants to adjust more easily when the conversation doesn’t go as we hoped.

In the church system

Nurturing a spirituality of surrender, mercy and grace rather than law and judgment. Grounding the parish in norms derived from our Anglican ethos and Benedictine spirituality (listening with the heart, humility, no grumbling in combination with taking counsel)

An earlier posting that explores the above from a slightly different standpoint is - Caesura: Methods for “taking counsel” ..... Part One

Collaboration – dealing with resentment

A well done collaboration process can help a parish community more effectively cope with underlying resentments and annoyances. For example, in the incense case – there will be people who are thinking “Why did you join a parish that uses incense routinely if you can’t stand it? Why do you think you now have the right to impose your views on the rest of us?” or “If you don’t like the incense here at Saint Mark’s, Philadelphia there are four other parishes in walking distance without incense. Go there!” or “I understand that you want to attend Saint Mark’s because of the wonderful music. You can walk two blocks and go to Trinity with its great music.” In a parish like Saint Mark’s the number of people wanting an incense free parish will be few.

The overwhelming majority of parishioners will see incense in the Liturgy as a “given.” So, what are examples of likely resentment from the other side? – “Incense makes me ill. Is that okay with you?” or “Incense is not true inclusiveness. Saint Mark’s is known for accepting and welcoming people.” Or “There really are many people upset by the incense.”

There may be reasons to not attempt a collaboration even if it will more effectively address underlying resentment and nudge the parish community into a healthier place. For example,

- There’s not an obvious way out of a basic win/lose, or lose/lose (compromise), in the situation. If the parish only has one primary mass at 10:00 am a rector in a parish like St. Mark’s would wisely decide on the use of incense at all celebrations. Time to use the rector’s authority.

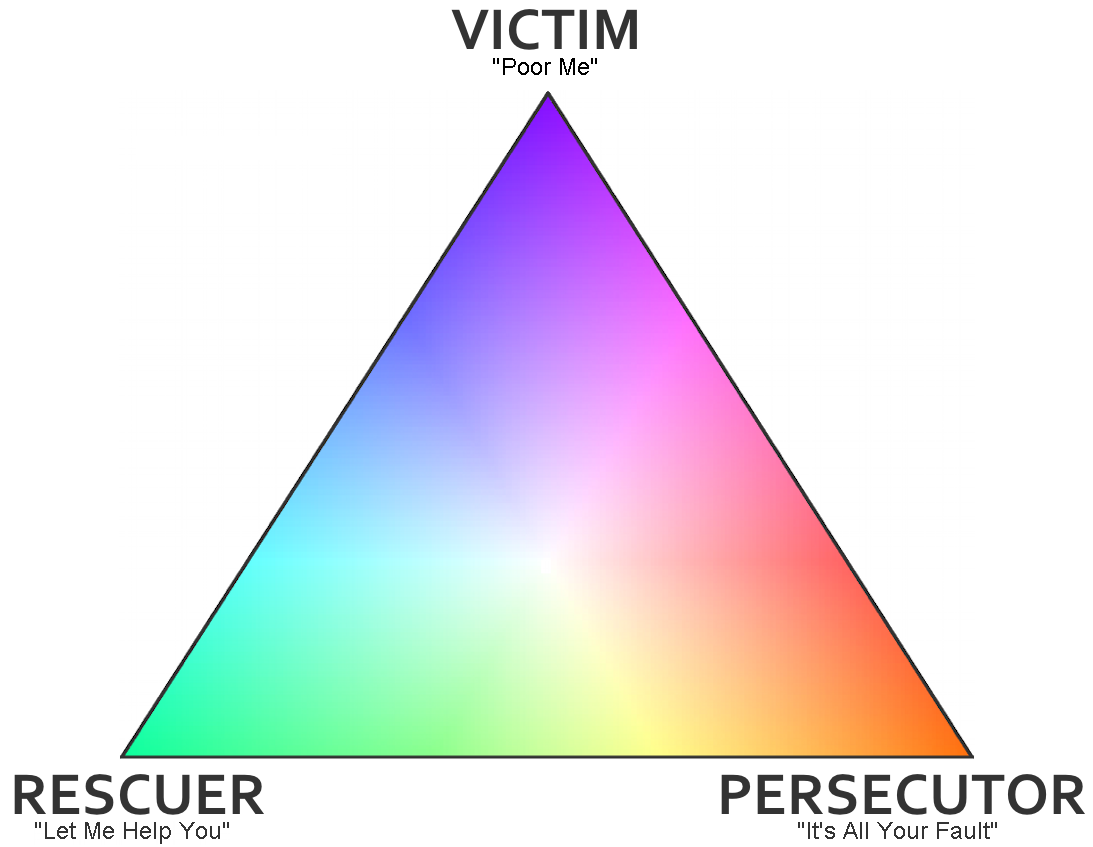

Too many people are trapped in a Drama Triangle. There’s an intense commitment to being the victim and/or the persecutor and/or rescuer. In the triangle people tend to move from one emotional position to the other and back again. If we can’t reasonable anticipate that people will move beyond that drama, we are better off avoiding a collaboration attempt. There’s too much likelihood of it backfiring.

Too many people are trapped in a Drama Triangle. There’s an intense commitment to being the victim and/or the persecutor and/or rescuer. In the triangle people tend to move from one emotional position to the other and back again. If we can’t reasonable anticipate that people will move beyond that drama, we are better off avoiding a collaboration attempt. There’s too much likelihood of it backfiring.- The issue is not one that people have strong feelings about (so you will not get the necessary investment to do the work)

It is already a high level conflict. That's not just about some people having strong feelings and opinions. It's an assessment to be made using models such as the Relationship Cycle and/or Conflict Levels.

It is already a high level conflict. That's not just about some people having strong feelings and opinions. It's an assessment to be made using models such as the Relationship Cycle and/or Conflict Levels.- The conditions needed for effective collaboration are simply too weak (see above for “How do we set up a collaborative process?” and below for “Other conditions that will help collaboration.”

At this point the time and energy is needed to deal with a crisis or another developmental opportunity.

Other conditions that will help collaboration

- A leader willing to be firm and directive about the process that is needed.

- Setting a tone of empathy, curiosity and openness.

- Presenting the situation as one that is a problem or challenge in our common life.

- Paying attention to the process reality that an owned, sustainable outcome is more likely if it is built upon the base of adequate and useful information, an exploration of many options, and a sense of free choice.

- A specific process in which the positive underlying concerns of people get identified and tested.

The questions parish leaders might ask themselves is these, “Is there enough of the parish community that would enter into such a process of learning and openness to make this work? Am I willing to do that myself?

rag+